We have evidence on the best ways to measure learning, in alignment with SDG 4, which can help ministries of education know where they are making progress and where they need to adjust policies and practices. A new tool, the Learning Data Toolkit, gives countries access to all these resources and allows them to provide feedback on measuring what matters.

This blog was co-authored by Silvia Montoya (UIS), Hetal Thukral and Melissa Chiappetta (USAID), Diego Luna-Bazaldua and Joao Pedro De Azevedo (World Bank), Manuel Cardoso (UNICEF), Rona Bronwin (FCDO), Ramya Vivekanandan (GPE) and Clio Dintilhac (BMGF).

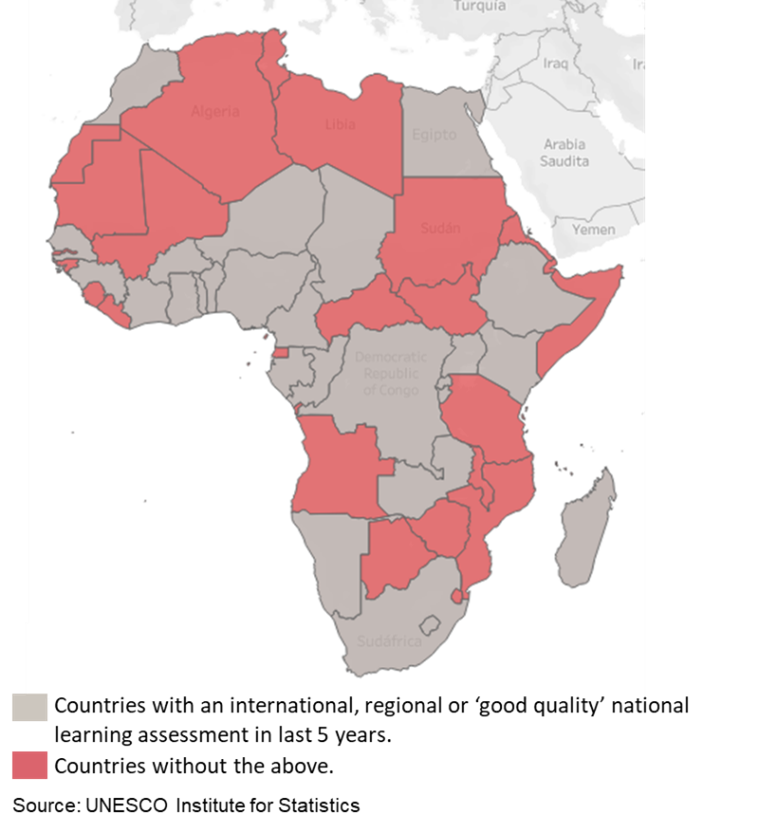

We are in the midst of a global learning crisis: Reports on learning poverty suggest that 7 in 10 children in low and middle income countries (LMICs) do not know how to read with comprehension by age 10. However, in most of the developing world, we can only estimate how many children know how to read as we do not have reliable data to measure outcomes and progress on learning over time.

In 86% of LMICs, we do not know how much learning has been lost due to COVID school closures. If we are to measure progress across and within countries across years, we need data that measures what matters and that is reliable and comparable over time.

Thankfully, we are closer than ever before to this objective. We have political momentum: Education partners came together recently at the United Nation’s Transforming Education Summit to make a commitment to action on foundational learning, including committing to better data on learning. Most importantly, there are now methods available to countries to strengthen their assessments and anchor their measurement in expert advice.

Why has the collection of comparable, reliable learning data been so difficult?

Despite the growth of national and international assessments, collecting comparable learning data over time and between countries is no simple feat. This is because most assessments:

The solutions: A common framework and methods that build on countries’ existing assessments

Under the leadership of the UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) and with support from partner organizations, solutions have been developed in the last few years to enable countries to improve their learning data, building on their existing assessments:

Achieving this goal in time will require an acceleration of the use of these solutions to strengthen existing assessments and use them to measure progress reliably.