By Brendan Murray | 3 February, 2018

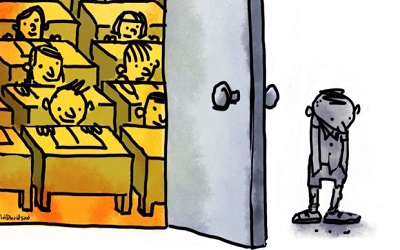

Nearly a million Victorian children returned to school last week. But thousands did not. Exclusion is a cruel yet quietly accepted component of our education system.

Last year the Victorian Ombudsman reported that hundreds of children are formally expelled from school, and thousands more are excluded by other means. Last week, while lunches were being packed and the traffic thickened, I was thinking of those barred from school. I was thinking of how we’re failing these children – whose development is already impaired – by enforced social isolation and lack of access to education. And in doing so, we’re causing them more developmental harm.

The 2017 Ombudsman’s report, Investigation into Victorian government school expulsions, described the damaging impact of exclusion on the expelled child. This child could be as young as four or five. They probably have a disability. They might be in out-of-home care. Often they identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander. They’ve likely experienced significant trauma.

As to the involvement of the Victorian Department of Education and Training, the Ombudsman exposed failure in terms of legal compliance, keeping adequate expulsion data, and overseeing and monitoring formal and informal expulsions. She urged the minister and department to overcome entrenched and accepted exclusionary behaviour that exists within the government school system.

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 states as its first principle for government education in Victoria that “the state provides universal access to education”. The second principle is that “every student has the right to attend a designated neighbourhood government school”.

The legislation does not say that universal access to education for compulsory-aged school children will be revoked if a child behaves in a way that doesn’t comply with the acceptable social or emotional development of his or her peers. Nor does it contain any proviso that a child’s right to education in Victoria is forfeited should that child not meet the accepted behavioural norms of their peers. Yet, this is the way that our government school system operates.

The Ombudsman recorded stories of excluded children and their families, describing their experiences as “heartbreaking”. These children were not bad children, she said, but children “who had bad things happen to them”. The report shone a spotlight on how it’s the most vulnerable, arguably those most in need, who are excluded en masse from schools by formal expulsion and, worse still, informal expulsion leading to complete disengagement from education.

Formal expulsion is supposed to follow departmental guidelines so that the excluded child remains within the education system and attends another school. Informal expulsion sees the school letting the child or family know that they are not welcome. It’s this second form of expulsion that’s rampant in Victoria.

Time and time again, children and families have told me they were convinced to leave school with comments like “you don’t fit in here”, or, pitched more favourably, “this way you’ll have no mark against your name”.

The Ombudsman acknowledged “the behaviour of these children may be extremely challenging” but said surely it’s “within the power of our education sector to support these children”.

I’ll go further and say it’s the very purpose of school to provide education for children to learn not only numeracy, literacy and knowledge-based skills, but also to learn behaviour and how to work together to overcome problems. It’s certainly not the purpose of school to teach someone to go away and give up because they’re not worth it. Nor is it to teach the remaining students to stand by and watch while their more vulnerable peers fall through the cracks.

Last year, Education Minister James Merlino announced the government’s plan to act decisively and “implement the Ombudsman’s recommendations, and support principals, teachers and students”. He added that “you can’t just give up on kids”. He pledged $5.9 million to assist schools help students with behavioural issues avoid expulsion and stay engaged. He promised greater departmental oversight of and intervention in expulsions, and an overhaul of the way expulsions are monitored, as well as a review of the appeal process.

This school year, the Andrews government has the opportunity to rectify its failures and create its own legacy by recalibrating the current system to one of inclusion and legal compliance. Let’s hope it does, because the stakes are high. For these kids. And for all of us.

If we don’t stop this exclusion and give these children the education they need, expect more headlines about gangs, more news about our broken youth justice system. Expect more heartbreaking stories of isolated children and their families.

Every child has the right to education. They’re entitled to an education directed to the full development of their personality. Let’s deliver on this and offer inclusive education in Victoria. Because this time next year, I want to see all Victorian children returning to school.

![[Preliminary Report] CRNA Collaborative Research for Exploring Factors Nurturing"Happy and Resilient" Children among Asian Countries](https://equity-ed.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/1725672182698.jpg)