when the fighting between the Tatmadaw and the People’s Defense Force began to affect the communities of Myanmar’s Kayah state in 2019, a young girl scrambled to take with her the belongings that seemed most important. Thinking she might need something to read on the long journey, she quickly grabbed her school textbook and fled.

Two years later, in early May of this year, an activist fleeing Yangon for an internally displaced person (IDP) camp in Kayah State found the girl with the same textbook, now worn from repeated readings. With limited options, it became her entertainment for long hours spent at the camp.

Moved by the tattered book, now a few grades below the girl’s education level, the activist did the only thing he could think of – call a friend in publishing.

“At that time, I was depressed, I didn’t want to do anything because of the coup,” said Rhi Zan about receiving the phone call. As managing director for Third Story, a social enterprise and publisher of children’s literature, she’s coordinated over 18,000 donated storybooks since May.

“He said that the girl from the IDP camp really needs storybooks, they don’t have any entertainment books, so I said okay, I have to work for them.”

Though only a few hundred of Third Story’s donated books this year are in minority languages, Rhi Zan says these are rare resources in remote parts of the country. As Myanmar’s minorities are at the brunt of the military’s attempt to suppress ethnic cultures in the diverse country, the February 1 coup has sparked a renewed momentum behind language preservation projects.

Many of the fledgling ethnic language initiatives in post-2015 Myanmar under the National League for Democracy (NLD), such as those seen in publishing, universities, and even the widely criticised “30,000 kyat” programme teaching these languages in government schools, came to a halt following the coup. But now, with the Bamar majority increasingly conscious of minority perspectives in the wake of the putsch, activists are working to ensure that these hard-to-find resources don’t go missing for good, keeping them alive even while in hiding.

“Their language is valuable, that’s why he or she tries to help us to translate their own languages,” Rhi Zan said of Third Story’s authors, who come from several ethnic minority backgrounds.

“Most of them are against the military, and when the military realised they’re doing something against them, they have to change their phone number, they have to run away, they have to leave their house.”

Myanmar boasts more than 135 officially recognised ethnic minorities, many using multiple dialects to make up the country’s 100 languages. But until 2014, when a new education law was passed, teaching them in government schools was banned for nearly 40 years under the military dictatorship. Amidst this strict censorship, literature and teaching materials produced in ethnic minority dialects became rare, placing the languages at risk.

Third Story’s own mission to produce children’s literature in ethnic minority languages began in 2015, shortly after the landmark election that saw Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD sweep to power in an era of hope. Today, among the organisation’s 74 published books are Shan, Pa-O, Jinghpaw, Karen, Mindat and other minority language stories, in addition to Burmese and English.

Third Story’s operations were halted following the February 1 coup until May. But now, two months after resuming their work, the organisation has secretly donated literature to more than 100 different places affected by violence. Among these places are IDP camps, areas occupied by ethnic armed organisations (EAO) and those impacted by conflict, including Rakhine state, a place carrying personal significance for Rhi Zan.

“When I was really young, I spoke Rakhine language. At that time, a lot of Burmese people didn’t understand what I said, so they also discriminated against me,” she told the Globe. Although as an adult she struggles to speak Rakhine, Rhi Zan hopes that children can not only gain proficiency in their local language, but empathy as well for others who haven’t.

“I want to encourage them to speak their own languages, and I want other children to understand his or her situation,” she said. “Maybe they have different backgrounds, maybe they have different situations which have made them not able to speak their own language.”

Although creating these stories isn’t easy, Rhi Zan says new books in minority languages are in the works. Her mission is inherently politicised and carries risk, one she’s acutely aware of from hiding herself. She says, since the coup, receiving illustrations and writing from authors has been more challenging through hiding and internet outages.

“It’s not easy at all, [ethnic language content] is very difficult to find. Even though we have been producing a lot in ethnic language, whenever we try to produce it again, we face many difficulties,” she said.

“It is more difficult than ever because we lost contact [with authors and illustrators]. I had to change my phone number because [the military] can trace me. If you want to translate in your own languages, it means he or she is an activist.”

Before February 1, students across Myanmar could be seen walking the path to school, a colourful, woven bag at their side swollen with the morning’s textbooks, their worst fear being late for the morning assembly or forgetting a pen.

Today, they play a crucial role in the country’s anti-coup Civil Disobedience Movement by organising protests, occupying streets and even distributing news during internet blackouts. But when the military attempted a reopening of schools and universities on June 1, few students showed up in protest and for fear of their safety.

But alternatives are stepping in to fill the educational gaps left by the coup, with students now having the option to log on to low-cost online classes via Spring University Myanmar. Named after the country’s so-called Spring Revolution, academics and professors at the online school offer classes on federalism, ethnic culture and history, as well as languages like Chin, Karen, Mon and Shan.

It was the brainchild of two CDM activists, like co-founder Min, who wished to go only by their first name. The university began by opening International English Language Testing System courses, quickly attracting 150 students in May.

“A lot of students are hopeless and they don’t have any continuous education or those kinds of steps,” said Min, referring to students boycotting universities re-opened by the military.

Min saw opportunity beyond basic English courses and began to offer what’s now eight different schools of study, including a law school, when he saw the political climate changing. Min says minority language courses became a natural step in addition to ethnic minority culture classes. As the CDM grew more socially aware, they quickly found that ‘mainland’ Burmese students were eager to educate themselves on ethnic minority culture they weren’t aware of.

“We had complicated issues before the revolution, the civil wars have been going on for decades. People from the mainland weren’t really aware of those kinds of issues until this coup happened,” he told the Globe, referring to those from the Bamar majority concentrated in the centre of the country.

“When people know the truth, they really want to know about the ethnic minorities, they’re like our siblings. A lot of evolution happened during this process, so I think that’s a good transition.”

Although the school has yet to receive any official accreditation or the ability to give degrees, Min says the endeavour is symbolic, and he’s found no shortage of enthusiasm for it. While the school has only been open for two months, they’ve had nearly 2,000 students enroll.

Min says he feels like the initiative struck a chord with students looking for ways to continue their education in the absence of official means. The Facebook page has garnered more than 51,000 likes, and CDM influencers are promoting the initiative. Although most students are from Yangon and the online nature makes it difficult for areas lacking connectivity to join in, he said there are some students from other states as well.

Despite the school’s popularity, or perhaps because of it, the threat of military harassment is never far away. Teachers are largely recruited on a volunteer basis, and money from classes is donated to IDP camps, conflict zones and CDM staff.

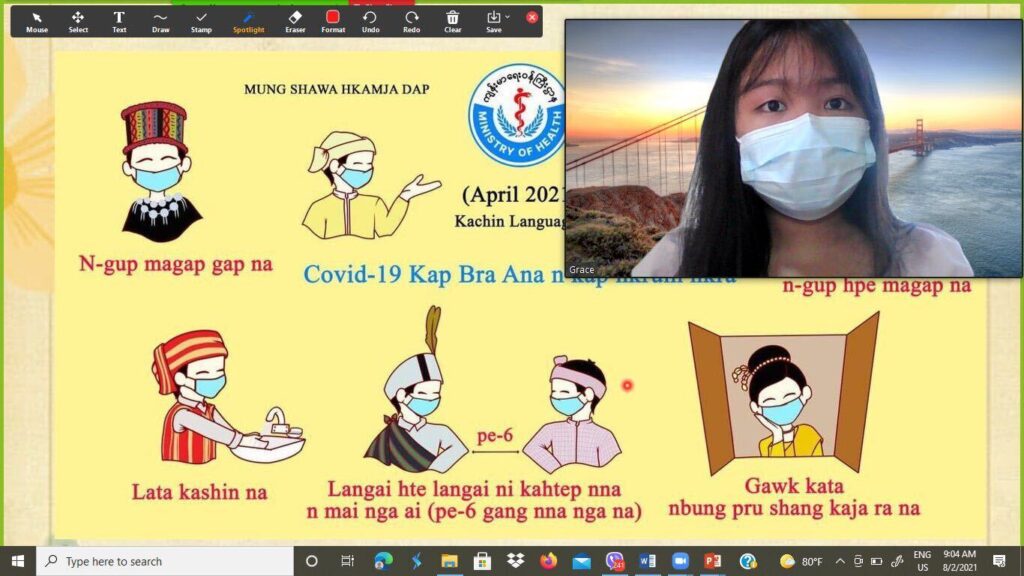

“They’re trying to hunt all the people related to the activities against them, so we have potential threats as we begin,” Min said. “All the teachers have to wear masks when they’re teaching, and they can’t reveal their identities. We also have code names, nicknames, we just have to use that, and they can’t reveal their locations as well.”

Grace, a former English teacher who only goes by her first name, teaches a course on her native Kachin language. She said this has given her perspective on how interest in minority languages and culture has shifted since the start of the coup.

“I was a bit hesitant to teach at Spring University because of my safety,” she said. When she attended university in Yangon in 2014, she said there was little interest or concern in the civil wars going on in her home state. But since the beginning of the coup, she said there’s been a renewed interest in her culture.

“When I teach something [now], they are really eager to know and eager to learn about it. That was the thing I enjoy about teaching the class. The people’s reaction is really different from 2014 to 2021.”

It’s estimated that up to 90% of Kachin state’s population is Christian, and Grace says Kachin language education is tightly intertwined with the church, as many kids grow up learning to read it by using a Kachin Bible at Sunday School. But through the years, programmes and summer institutes have grown.

“The [language] programmes are more popular these days, not when I was young,” she said. “We didn’t have a Kachin language programme at school, so we don’t really have a chance to [learn it].”

The election of the NLD in 2015 on a progressive platform saw the growth of ethnic language programmes in government schools. But underfunded and sparse, criticism levelled at these initiatives was for many symbolic of a wider complacency and broken promises around a government inclusive of ethnic minority voices.

Following the coup, with a seemingly renewed sensitivity to ethnic minority issues, ousted lawmakers and pro-democracy politicians embarked on efforts to rebuild with a more representative government. Creating the National Unity Government (NUG) on April 16, among their platform policies is an improvement on funding and implementation for minority language education, a goal reflected by their diverse ministry staffing.

NUG Ministry of Education deputy minister Ja Htoi Pan, whose own background is in Kachin education, says the right to language education is a basic step in democracy. Growing up in Kachin state during the military dictatorship years, she still recalls how her own language was heavily politicised.

“When we speak Burmese, we have accents, so people would lose their accent to not be identified as Kachin or a minority,” she said of her university days in Mandalay and Yangon, when ethnic language literature and language faced heavy censorship.

“There is so much fear among people to talk very strongly about their identity, so much fear.”

In recent years, Ja Htoi Pan’s home state of Kachin State has been particularly active in preserving ethnic language education, even developing their own university, the Mai Ja Yang Institute of Education, in 2015. Among its courses are Jinghpaw language, and educating future ethnic minority language teachers.

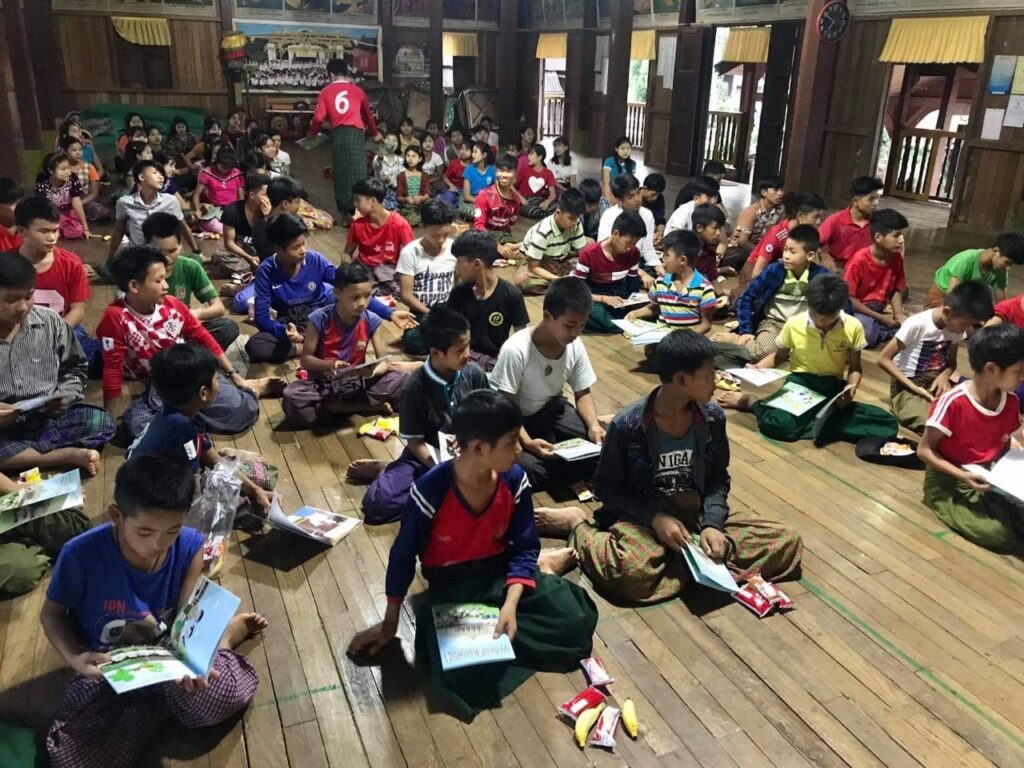

Situated on the border of Kachin State and China, it was started by the Kachin Independence Organisation to protect the future of its students’ education when a 17-year ceasefire ended in 2011. School principal La Raw says that the school has seen increased enrollment due to the protests and closure of government schools in the region since the coup, with the number of students increasing from 500 to 800 during 2021.

La Raw says that minority cultural associations like Mai Ja Yang Institute of Education have played an important part in supporting language initiatives and preserving them.

“Education departments are starting to do mother tongue-based language education because we’ve come to see that for children, young learners, this is a much better approach,” he said. “This method can preserve our languages as well, so we see these two as very important.”

For some, the increased prevalence of mother tongue-based learning signifies a larger change in society, with even the NUG’s proposed education curriculum including minority languages. Many see this as a step towards finally creating a representative government.

“It could be a political statement, especially as there’s been a call and public interest in federalism, it’s been really big. This new language initiative, people are starting to have an interest in minority people,” Ja Htoi Pan said.

“This has never been the case, it’s a very significant and important phenomenon.”