Silent teachers and embarrassed parents have kept the issue of how best to teach students with learning disabilities in the shadows, when what we need is an open dialogue.

Jun 29, 2018 | 6-min read | Commentary | By: Luc Pauwels, Educator

As a teacher, we all know that children can struggle from time to time, whether with a difficult math problem, while reading a challenging text out loud, or when writing an essay. However, for some children, certain subjects are consistently more challenging than others: This can be sign of a learning disability or behavioral disorder, and may even be a symptom of a serious neurological issue.

A learning disability is not a problem of intelligence, motivation, or laziness — it is a problem with how the brain functions. Children with learning disabilities receive and process information differently from others, which impacts how they see, hear, and understand things.

Yet as the international vice principal of a well-regarded primary boarding school in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, I have noticed that many of my fellow staff have shied away from the subject. So, in order to highlight this important issue, in early March I began conducting classroom observations of three students I had identified as potentially in need of additional support — all of whom are boys between the ages of 7 and 8.

“What are you drinking?” I remember one of them asking me in Chinese. “Coffee,” I responded, meeting his faint smile with a warm one of my own. But the boy’s facial expression abruptly changed, revealing puzzlement, uncertainty, and frustration. It was clear that he hadn’t understood my response, and we both fell silent.

Watching these kids struggle — knowing that they had the intelligence to perform the tasks asked of them, just not the mental tools to process them smoothly — made a deep impression on me.

Dealing with an entrenched taboo requires patience, endurance, and above all a passion for the well-being of the affected children and their parents.

– Luc Pauwels, educator

That night I struggled to fall asleep. My mind kept wandering toward the questions spinning around in my head. Was it my place to try to diagnose these children with a specific disorder or disability? Should I be trying to find proper solutions like therapy and special needs programs for them? I realized that the answers to these questions could only be found by talking to my teaching staff — as well as to the school’s leadership — about what I had seen.

The next day I struck up a conversation with my Chinese counterpart in the office. “Have you noticed that boy in grade two who speaks in a loud monotone, struggles with simple interactions, and engages in repetitive actions?” I asked. My colleague just nodded and answered in the affirmative, so I decided to press the issue. “What problem do you think he has?” I asked. A long silence followed, and for a time it seemed like there would be no answer.

Finally, she responded, but in a tone that made it clear that the topic was off-limits for further discussion. “You are stirring up the most difficult issue in education,” she said.

My classroom observations and conversations with other staff members convinced me to make raising awareness of the educational needs of children with learning disabilities and behavioral disorders my personal mission. So I went to my friend Zhu Nan — an associate professor specializing in special education and special needs teacher training at Central China Normal University — for more information.

“China adopted the concept of inclusive education in the late 1980s,” she told me, “and it educates about 50 percent of special needs children in regular schools. At present, each region has established special education resource centers to provide various kinds of support and services to special needs children in regular schools.”

The reality at my school was far less rosy than the picture my friend had painted, however. The three students I had observed had all been labeled non- or under-performers, and were being given extra daily academic tutoring sessions during break times. “This is a big and difficult topic,” Zhu said, echoing the words of my colleague.

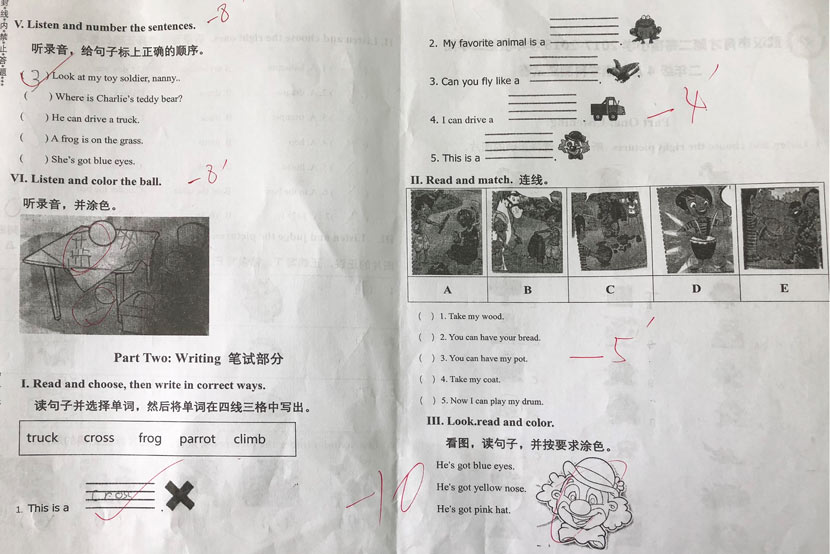

An exam taken by a student from Yu Cai No. 2 Primary Boarding School, Wuhan, Hubei province, April 27, 2018. Courtesy of Luc Pauwels

Finally, after several weeks of beating around the bush, I asked Zhu what she thought I should do about the three students I had been observing. She responded by offering to visit the school and observe and test the children in question before helping me decide on a program best suited to their needs.

I knew that I would have to approach the school and parents carefully, so I bided my time, waiting for the right moment to ask for approval to invite an outside expert into our school.

One Monday morning, I approached the mother of one of the boys I had been observing. “I would like to talk to you about your son in private,” I said. She just nodded without saying a word. I went on to tell her that my daily classroom interventions — combined with the support provided by her son’s head teacher — had begun to show positive results. Her son was gradually doing better in class, scoring high marks in English, picking up Chinese writing, and — most importantly — coping slightly better with his frustrations and anxiety. Three weeks later, his mother walked up to me and said, “Tell me what you have on your mind.” I told her that an expert had offered to help her son and another two students. The mother beamed, her eyes shining, and repeatedly thanked me.

My next move was to involve the school’s leadership — though the topic is still seemingly taboo. I was told in no uncertain terms that China’s examination-oriented education system does not wait for students with learning disabilities. Students and teachers are under tremendous pressure to reach strict targets semester after semester, and the kids who fall behind usually stay behind. Meanwhile, teacher bonuses are frequently tied to exam pass rates. This creates an unfortunate situation in which teachers can easily grow frustrated with students who have learning disabilities, since these students’ struggles can cost teachers part of their paychecks.

Dealing with such an entrenched taboo requires patience, endurance, and above all a passion for the well-being of the affected children and their parents. Yet I believe that there is hope for students with learning disabilities, so long as educators move quickly to provide them with the right learning environment. However, my observations showed that school staff were hesitant to talk to parents about their children’s learning difficulties, while parents often felt too embarrassed or ashamed to open up about their child’s struggles. This unwillingness to openly discuss the issue costs everyone involved valuable time.

Recently, I suggested to the mother of the boy I had spoken to earlier that she try to open a dialogue on the subject of learning disabilities with the head principal of my school. Are her son’s learning difficulties persistent? Does he have any emotional issues? Is the material too challenging or the work too difficult for her child? Is it possible that he has one — or even multiple — learning disabilities? These may be uncomfortable questions to ask, but the only way schools might be willing to do more for students with learning disabilities is if parents start engaging them in an open dialogue about these issues.

In the meantime, I believe that schools should appoint or train one or more staff members to act as special needs teachers. In turn, these teachers must be allowed to discuss and make individual action plans with the parents of children with learning disabilities — covering diagnosis and special needs programs. Finally, schools should create an individual action plan for each student that details the responsibilities of both the school and the child’s parents, clarifies what — if any — external help is needed, and outlines a meeting schedule that includes sessions for revising the action plan. They should also keep the children in question informed about their progress.

As for the three boys I observed, I still visit them in their classrooms. “Can you talk to my mother on Friday about my progress?” one of them recently asked me. I simply nodded at him and smiled.

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A drawing by a student from Yu Cai No. 2 Primary Boarding School, Wuhan, Hubei province, April 2, 2018. Courtesy of Luc Pauwels)

![[Preliminary Report] CRNA Collaborative Research for Exploring Factors Nurturing"Happy and Resilient" Children among Asian Countries](https://equity-ed.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/1725672182698.jpg)