GEM Report | 05 February 2018

With the curtains of the third Financing Conference of the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) in Dakar, Senegal now closed, it is important to remember the context in which it was organized.

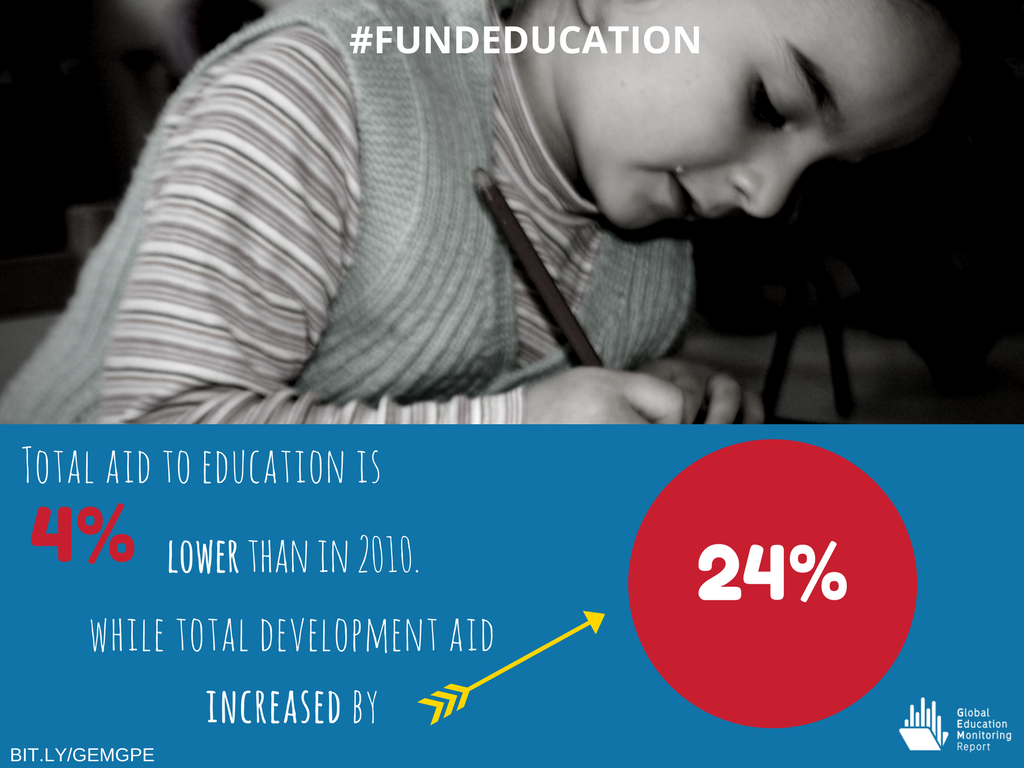

During the first half of this decade, aid to education stagnated even as overall funding increased by 24% in the middle of a financial crisis. In 2015, the international community agreed a more ambitious education agenda with additional cost implications. The Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report estimated an annual financing gap of $39 billion between 2015 and 2030 if low and lower middle income countries were to achieve universal pre-primary, primary and secondary education.

During the first half of this decade, aid to education stagnated even as overall funding increased by 24% in the middle of a financial crisis. In 2015, the international community agreed a more ambitious education agenda with additional cost implications. The Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report estimated an annual financing gap of $39 billion between 2015 and 2030 if low and lower middle income countries were to achieve universal pre-primary, primary and secondary education.

(Not) All I see is dollar signs

Aid to education remains a significant source of financing, at least in low income countries. However, aid is valuable not only because of the dollars spent but also because of the support it can provide to education systems, if effectively provided. The GPE still represents a small share, by the latest count just 12%, of total external funding to basic education. But as the leading global fund for education, it has played a constructive role in targeting aid to countries most in need, aligning with country priorities, and engaging a broad group of stakeholders in reviewing the implementation of national education plans.

The GPE had set itself the target to quadruple its disbursements to its developing country partners by 2020. With increasing evidence on the importance of education not only as a human right but also as a catalyser for achieving the other Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), one of the key questions in the audience at the conference was: what were we waiting for?

In the end, it is estimated that between $2.3 and $2.5 out of the targeted $3.1 billion will be committed for the period 2018-2020. While short of what was requested, this replenishment round has raised up to $400 million more in absolute terms than the last round for 2015-2017.

Will the international community be looking back at the conference as an event that helped stop the decline of education in the order of international development priorities? It is difficult to know as it all depends on whether aid to education overall is also going to rise in coming years or whether GPE will simply command a bigger share of the same level of total aid to education.

But the smooth organization of the event, the impressive presence of political leaders and advocates for education and the fact that partners were given space to voice their thoughts and set out their plans, helping to keep alive the spirit of partnership, were all positive signs.

The European Commission in absolute terms and Norway in relative terms emerged as the most generous donors. Other donors demonstrated their trust in the future of the Global Partnership by committing higher contributions than in the last replenishment round. There was a pledge of $100 million from the United Arab Emirates, the first from a non-OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) member. Expectations that China might have contributed, though, were dashed. A firm commitment from the United States is still on the cards.

By 2020, the United Kingdom will continue being the largest contributor since the establishment of GPE. However, it made 30% of its latest pledge conditional to results. The GEM Report, which launched a policy paper on results-based financing at the conference, has urged caution with the wider application of such approaches. However, the disbursement linked indicators, which have been used by the GPE in some of its partner countries, are rather carefully selected and could provide positive incentives.

Who is accountable?

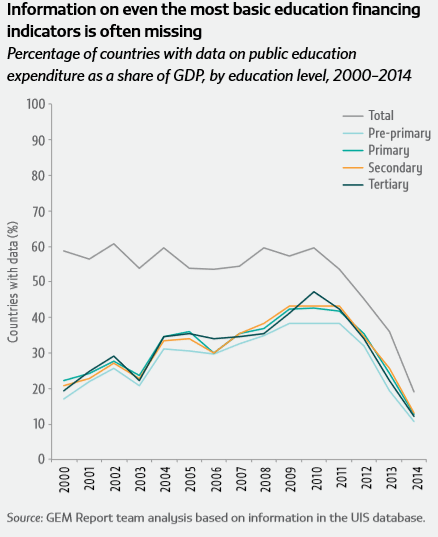

Domestic pledges were also counted. These took the form of a commitment to increase  the share of budget to education to over 20%. As with the last replenishment round, it is more difficult to monitor the fulfilment of these pledges. It was not clear what part of that increase would end up financing basic and not other levels of education. And information on public expenditure is neither reliable nor up-to-date, although GPE is collaborating with UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) to improve data availability.

the share of budget to education to over 20%. As with the last replenishment round, it is more difficult to monitor the fulfilment of these pledges. It was not clear what part of that increase would end up financing basic and not other levels of education. And information on public expenditure is neither reliable nor up-to-date, although GPE is collaborating with UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) to improve data availability.

There is no existing study of domestic pledges over 2015-2017. However, as we had commented at the time of the last replenishment, these pledges had not been very credible and developing countries were certainly less successful at keeping their promises than donors.

But if domestic pledges are fulfilled this time over 2018-2020, it is estimated that $110 billion would go to education. This is a reminder that even in the poorest countries, external financing is only a very small part of the picture.

While the Presidents of France and Senegal were cheered as co-hosts of the conference, it was the president of Ghana who received the strongest round of applause when he reminded the audience that rich countries had to help put an end to $50 billion worth of illicit financing flows that was depriving education from valuable resources. Adding to this, the Foreign Minister of Norway said that his country would fund not only education but also the development of poor countries’ capacity to raise domestic resources.

What next?

With a smaller pledge than planned, one important question is whether it makes sense for the Global Partnership for Education to extend its reach from 65 to 89 countries, which was one of the objectives of the replenishment. One of its most distinguished characteristics was the ability to target countries most in need and certainly an extended country coverage is only ever going to dilute this effort.

The conference also addressed data and monitoring issues. The Education Data Solutions Roundtable was a highly publicized initiative but more as a symbol of drawing private funds into the Global Partnership rather than for its real merit, which is to bring into education the idea of a national network of data producers and users that was first implemented in agriculture.

There was no discussion over the continuing challenge that donor resources to the GPE are not yet identifiable in the OECD DAC database of aid flows. This makes it hard to attribute any education advances in developing countries to the activities of the GPE. The progress promised in 2014 has not yet materialized although efforts continue.

Finally, on the bigger picture of SDG 4 monitoring, the GEM Report joined a panel to support the investment case for data collection that UIS put together in January. Following this investment plan would help target external and domestic funding to those activities that are most critical for reporting on the SDG 4 global and thematic indicators, namely learning assessments and household surveys, and avoid waste and duplication of resources.

Finally, on the bigger picture of SDG 4 monitoring, the GEM Report joined a panel to support the investment case for data collection that UIS put together in January. Following this investment plan would help target external and domestic funding to those activities that are most critical for reporting on the SDG 4 global and thematic indicators, namely learning assessments and household surveys, and avoid waste and duplication of resources.

The challenge ahead

The third Financing Conference showed that partners approve of the efforts the GPE has made to bring them together for a common purpose. This is an achievement that is down to a lot of hard work by its Secretariat and Board. But after a pause to celebrate and take a breath, we all need to go back to the hard slog: there will be no sustainable development until all children complete and benefit from equitable and inclusive education of good quality. And yet, as of today, nine out of ten children in sub-Saharan Africa do not even achieve minimum proficiency in reading skills.