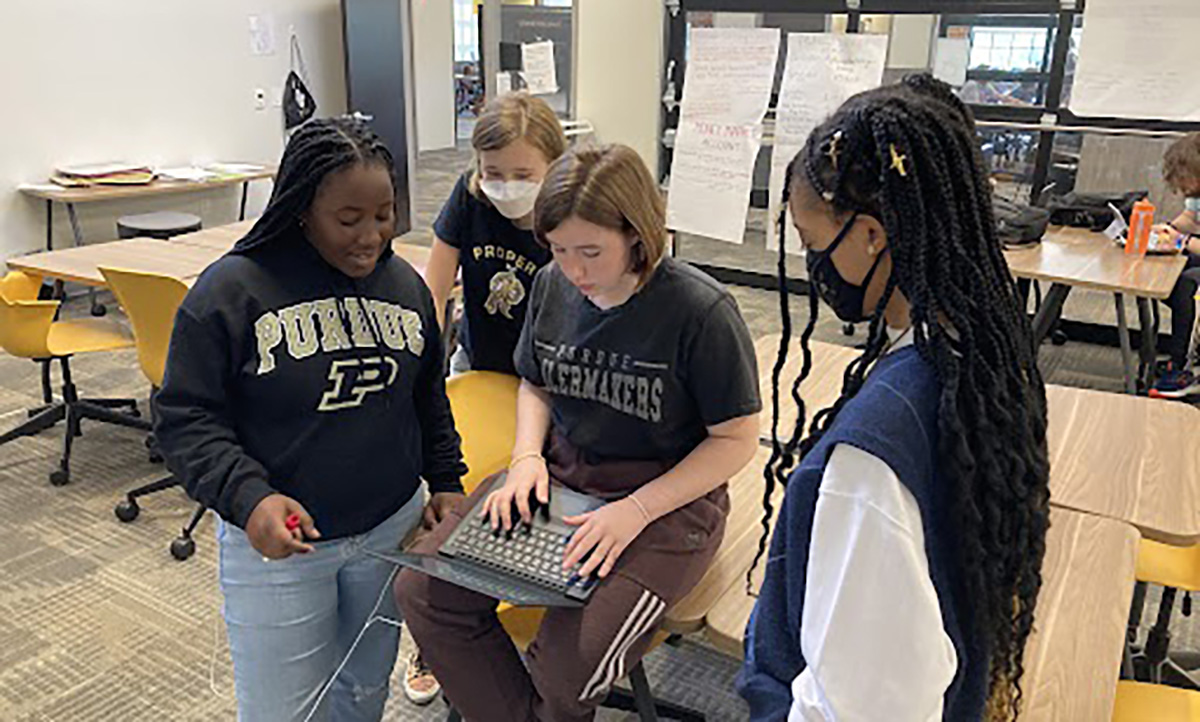

At Purdue Polytechnic, teens combine subjects & choose projects as part of early college exposure in hopes of ushering them into high-paying careers

This article has been produced in partnership between The 74 and the XQ Institute.

Indianapolis, IN — Raina’s ninth grade schedule at Purdue Polytechnic High School looked nothing like that of a typical high school student. Unlike most teens, she never attended single-subject, 50-minute periods like math, English and social studies. No bells rang when class was over. Instead, interdisciplinary projects and personalized learning are key at this XQ school in Indianapolis, Indiana.

This structure allowed Raina to choose a different schedule every six weeks, in six cycles over the year. During one cycle, she participated in a mock trial that required her to research previous cases, analyze evidence and build written cases. Six weeks later, she signed up for the next level and focused on presenting cases in front of a judge and jury in collaboration with local attorneys. She also took a journalism course that involved not just writing and researching articles, but learning the ethics of the craft. And in each cycle, Raina also took some online classes, such as Spanish, Latin and math.

It sounds overwhelming — more like college than high school. But Raina, who’s part of PPHS’s Class of 2025, said the workload is very well paced. “They don’t give you a whole semester load of work to do in six weeks,” she explained.

PPHS is breaking the mold of traditional high school learning for a reason. Less than half of all U.S. high school graduates are ready for college or career, and a full 40 percent of 12th graders were below basic in math on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress. The achievement gaps are especially pronounced among students from low-income families and those who are Black and brown, because students from underserved communities have been historically and systematically neglected.

Former Indiana governor Mitch Daniels saw those disturbing patterns when he became president of Purdue University in 2013. The university teamed up with business leaders, the city of Indianapolis and the state to raise the number of students from underrepresented backgrounds attending Purdue University and going into STEM careers. They designed PPHS and it was among the winners of XQ’s challenge to rethink the U.S. high school experience. It opened in 2017 with a nontraditional schedule emphasizing more personalized learning and engaging, real-world projects aligned to state standards and Indiana’s workforce development goals.

“The idea that learning needs to be time-bound, or that every student learns in the same way in increments and goes from class to class is antiquated, and doesn’t really serve students well,” said Keeanna Warren, the school’s associate executive director.

Since graduating its first class in 2021, PPHS has sent more than twice as many students to Purdue as the entire Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) district, most of whom are students of color. The school now has three campuses (in Indianapolis and South Bend) and it reported cohort graduation rates of 83, 86, and 100 percent in 2022. By comparison, the typical graduation rate in IPS hovers around 72 percent.

In addition to project-based learning, PPHS students have personal learning time between classes to work with teachers — called coaches. This allows for differentiated instruction and targeted academic assistance. Throwing out the high school playbook may seem easier for a new charter school partnered with a top-notch university than for an existing school with an established culture. But many other U.S. high schools have hacked the traditional schedule to make learning more personalized and flexible. These include all of the XQ schools and partners, High Tech High charters, district lab schools like Building 21 in Pennsylvania and a consortium of public schools in New York.

Most importantly, experts say other schools can replicate these models.

There are Fewer Obstacles Than You Think

When switching up the traditional school day, “sometimes people think there are more barriers or requirements than there actually are,” according to Laurie Gagnon, director of the Aurora Institute’s CompetencyWorks program.

School leaders often feel constrained by the Carnegie Unit, the century-old system that’s still the organizing principle for most U.S. high schools, with learning measured by seat time. However, there’s an increasing recognition that this system doesn’t serve all students, which is why XQ partnered with the Carnegie Foundation to spend the next few years developing a replacement for time-based learning.

In the meantime, Gagnon said interdisciplinary projects that combine material from different subject classes can easily meet state requirements. At PPHS, one industry project involved having students meet with public transportation officials to develop solutions that could serve the community better, using what they learned about population density and how it changed over history due to factors like interstate construction and redlining. To meet state standards, the school also schedules students into interdisciplinary classes. One called “the candy corn catapult,” for example, combines math and physics.

Various states and districts encourage schools to create innovative schedules. In Indiana, schools can request waivers from state mandates. New Hampshire and Oregon are among states moving to give credit based on factors other than seat time, according to the Aurora Institute. Some districts have created innovation zones through agreements with their unions. In Boston, pilot schools have flexibility around hiring, budget, bell schedule and curriculum. In New York City, the union contract allows school-based options if most teachers agree to a different schedule.

In-House Tech Expertise Helps, But Isn’t a Requirement

The traditional high school “master schedule” exists for a reason: functionality. Regardless of whether the school has 100 or 1,000 students, it can program the appropriate classes for every pupil while also ensuring courses align with student needs, the curriculum, and legal requirements.

But PPHS had no template when it did away with the master schedule in favor of more personalized learning. Staffers were scrambling in 2017 to give 150 first-year students different choices each week, in six-week cycles. The solution came from Andrew Zeller, a Purdue University graduate student in math who was on the PPHS team at the time. Zeller found Setmore, a software program typically used by hair salons and yoga studios. Signing up for an electric car project using Setmore was as easy as scheduling a trim and highlights. But he still had to program each student’s selections manually so they’d know their next week’s schedule by Friday. “I don’t think I slept on Thursday nights for two years because I was building the master schedule on Thursday night,” Zeller recalled.

Setmore worked well until the school’s staff and population doubled a year later with a new class of ninth-graders, causing everything to slow down. Thankfully, the next solution came from someone else in-house, engineering and science teacher Drew Goodin. He wasn’t a software programmer but he was able to get Google sheets to work with an automation app. He named the new system Drewber — his first name plus Uber.

Of course, most schools don’t have someone on staff with these talents. But Goodin acknowledged there is an old school alternative: “Issuing paper tickets to classes could be a solution to this problem too,” he said, adding that changing the schedule wasn’t as important as maximizing student learning through the optimization of coaches, students and space. Schools can do all of those things within the master schedule. They can also make smart use of time, space, and technology — one of the six XQ Design Principles researchers say can lead to more equitable outcomes for all pupils.

A Shared Vision Matters, and So Does a Collaborative Culture

At a school devoted to personalized learning, it’s important to create a culture that allows constant iteration, PPHS leaders said. In its second year, for example, PPHS tried building its own curriculum through an online tool. But that was a huge lift for the staff. Making too many changes “just about destroyed the school,” said executive director Scott Bess. Teachers grew frustrated. Some quit. Founding principal Shatoya Ward, who now serves as chief of school operations, recalled the staff demanding an intervention. But instead of a mutiny, they worked together. She recalled them asking, “What are we going to do about this?”

Gagnon, of Aurora, said that it’s critical to carve out space for teachers to learn, have opportunities for professional development, and be a part of the design process. PPHS leaders said they’ve absorbed this lesson. They began offering fewer courses to make the schedule more manageable. The school also switched from six-week to eight-week cycles in the fall of 2022, and it’s become less enamored with online learning. But constant iteration relies on a shared vision, Bess said.

“I’d say the biggest thing is, remember your why,” he explained. “In our case, we want to get more underrepresented minority students and low-income students able to access a place like Purdue.”

Listen to Feedback from Your School Community

PPHS’s vision for more personalized, project-based learning wasn’t just a challenge for its faculty. It also presented a hurdle for students and parents used to traditional grading systems and test prep. Each project is tied to specific competencies, such as problem-solving, analyzing sources and using a growth mindset, that colleges and employers identified as lacking among too many high school graduates. That’s why Warren said communication was critical.

“We had open forums and town halls to receive feedback from parents and share the ‘why’ and ‘how,’” she said. “Some parents remained skeptical through graduation, and that feedback was helpful for our team’s growth.” Over time, Warren said PPHS saw more teachers, parents and students buy in once they realized the school was working.

Victor, who graduated from PPHS in 2022 and now attends Purdue University—where he’s studying integrated business and engineering—said he enjoyed his high school’s variety and flexibility. At other schools, he said, “you’re put in a box,” with a routine that becomes redundant and tiring. Like many PPHS students, Victor took advantage of a summer program allowing him to attend Purdue University. He also took dual credit courses at another local college, giving him a leg up as a college freshman.

Since the onset of COVID-19, there’s been more interest in flexible approaches to learning. “I think the pandemic has opened up some questions about where does learning happen, and how do we document it,” Gagnon said. And PPHS could provide schools across the country with valuable answers to those questions.